Understanding College Persistence for First-generation College Students Living through COVID-19

Cassandra R. Davis, Ph.D.; Harriet Hartman, Ph.D.; Dara Méndez, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Jason Méndez, Ph.D.; Terri Norton, Ph.D.; Julie Sexton, Ph.D.; and Milanka Turner, Ph.D., / FirstGen Forward / September 08, 2020

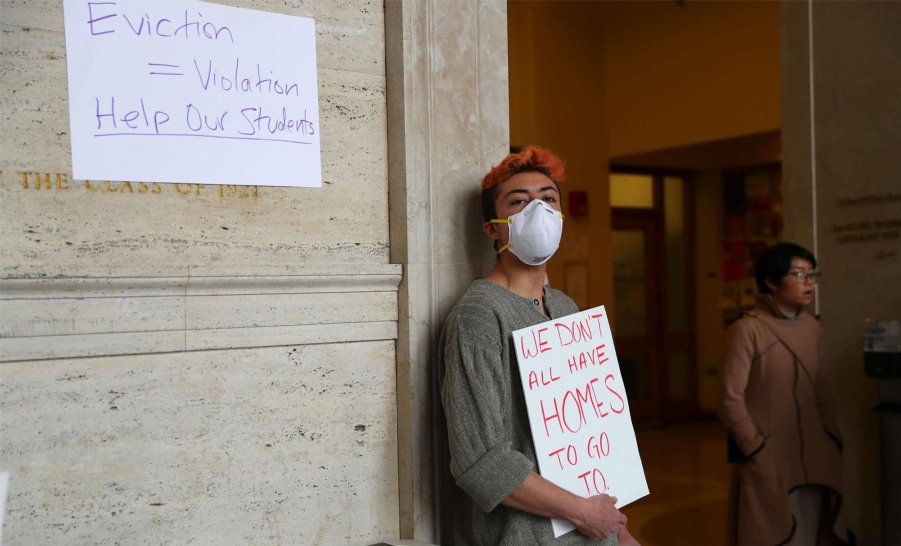

In recent years, many colleges and universities have prioritized recruiting first-generation students. As the COVID-19 pandemic upends campus life, schools across the country need to do everything they can to recognize the unique vulnerabilities of these students and support them through this unprecedented time.

Our research team1 studies how the disruption of campus life from COVID-19 is impacting first-generation students, and the initial results2 are worrisome. Surveys at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) and Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey found that first-generation students were much more likely to face obstacles in the sudden shift to remote learning.

For starters, first-generation students were more likely to be responsible for childcare. Many first-generation students returned to homes where younger children had also been sent home from school, creating additional household burdens.

Moreover, first-generation students were far less likely to report that their home environments were conducive to studying. In fact, more first-gen students at Rowan reported an unsatisfactory learning environment at home (45%) than reported an adequate one (30%).

None of this should surprise university administrators. We have long known that first-generation students are more likely to be low-income, represent communities of color, and arrive at college with fewer resources than their peers. Those same social forces inevitably impact their home environment and the resources available after campuses shut down in the spring.

For many, these compounding pressures deepened their anxiety about college and the odds of persisting. Students of every background reported increased feelings of loneliness after campus closures and stay-at-home orders. Roughly 80% of all surveyed students at Rowan and more than 90% of the first-generation students surveyed at UNC-CH said they did not feel connected to their peers.

“After examining all of the changes that have taken place because of COVID-19, I'd have to say the one that was most difficult for me was the fact that I so abruptly had to leave all of my friends behind,” one student told us. For a population that already struggles with feelings of belonging on a college campus, that sense of separation was only deepened by the spring disruption.

Then, of course, there’s the more immediate and practical worry about paying for school. At Rowan, the percentage of first-generation students who felt confident about financing their education dropped from 67% before the pandemic to 56% after the college closed in the spring. UNC-CH saw a similarly large drop, from 82% confidence to just 70% in the early weeks of the pandemic.

A variety of factors likely account for this decrease, including the sharp economic downturn that disproportionately affected low-income workers. Many students probably felt parents’ or guardians’ anxiety about coping with lost hours and less job security, but first-generation students are also more likely to work during college, either through official work-study programs or in off-campus jobs that help cover the cost of college. The shutdown of campuses meant the end of many student jobs, destabilizing already precarious personal finances.

After examining all of the changes that have taken place because of COVID-19, I'd have to say the one that was most difficult for me was the fact that I so abruptly had to leave all of my friends behind

All of this suggests administrators need to pay particular attention to their first-generation students if they want to maintain graduation rates and effectively serve those who could benefit most from completing their education on time.

A wealth of data already indicates that first-generation students are less likely to graduate than their peers, and we could see this disparity widen if campuses fail to act.

Greater flexibility with financial aid, including the use of grant funds to supplement lost wages and remote learning costs, would go a long way, as would increased support for programs like Carolina Firsts at UNC-CH and Flying First at Rowan, which both offer resources specifically targeted to first-generation students and their families. At a time when isolation from peers is a major problem, using those programs for aggressive outreach and mentoring can help keep students connected to college.

These concerns are only going to deepen as we head into a highly uncertain fall semester. Many campuses are once again expecting students to learn partially or fully online, often from their homes instead of campus. Many more may switch to remote learning if COVID-19 outbreaks worsen.

The results from our survey are preliminary and only reflect the first months of the pandemic’s impact, but we have every reason to believe that prolonged disruption will cause intensifying worries for first-generation students and their families.

For colleges that made the decision and the investment to get those students to campus in the first place, it’s time to uphold the implicit promise of seeing them through to graduation.

View Full Report

Footnotes

-

Authors are listed in alphabetical order. This COVID-19 Working Group effort was supported by the National Science Foundation-funded Social Science Extreme Events Research (SSEER) network and the CONVERGE facility at the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado Boulder (NSF Award #1841338). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF, SSEER, or CONVERGE.

-

We conducted a pilot study, as yet unpublished, and administered surveys between May and June 2020. We collected responses from 548 FGCS at UNC-CH (132) and Rowan (416). We also received surveys from 861 non-FGCS at Rowan. We will administer our first round of data collection September 2020 from FGCS across six university. Please send your queries to Cassandra R. Davis.