What a National Study on Collegiate Financial Wellness Can Teach Administrators About Supporting First-generation Students

Zayd Abukar M.A., The Ohio State University Office of Diversity and Inclusion / FirstGen Forward / April 10, 2020

The Study on Collegiate Financial Wellness (SCFW), administered by the Center for the Study of Student Life at The Ohio State University, yielded responses from over 28,000 students across 65 institutions in the United States. A brief from this study highlights three key findings related to first-generation college students at four-year public institutions:

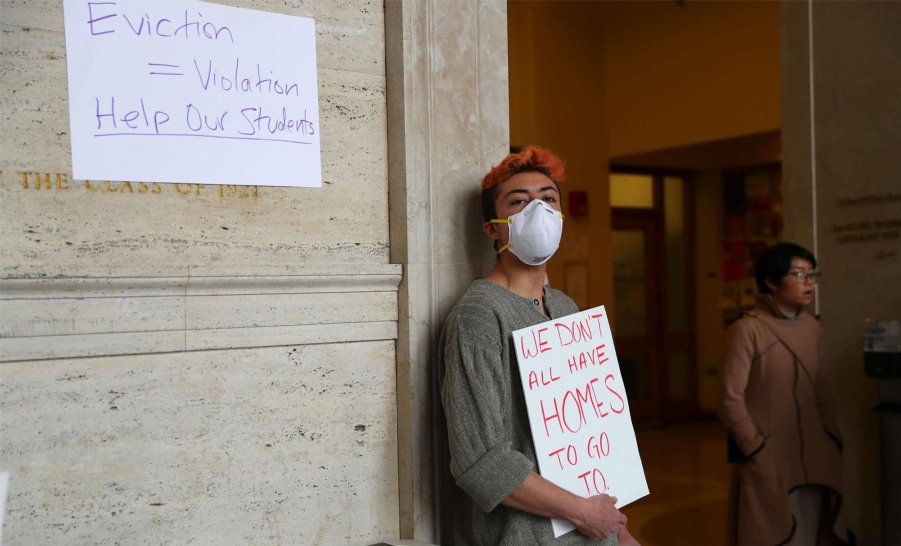

- First-generation students are significantly more likely than continuing-generation students to use loans, scholarships, credit cards, and wages to finance their education.

- First-generation students are less likely than continuing-generation students to use money from parents as a funding source.

- First-generation students report increased financial strain but lower financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and optimism relative to continuing-generation students.

Finances are a concern for most students, but they are particularly concerning for those who are first in their families to attend college. Based on the SCFW findings, we can surmise that first-generation students are more likely to have to work while they are enrolled to support themselves throughout college. We can also assume that the extent to which they can engage with co-curricular activities and campus resources will be limited.

Therefore, our task as academic or student affairs administrators is not simply to increase first-generation outreach efforts. Rather, we should also be examining how we can meet them where they are to increase their persistence, retention, and completion rates.

To this end, there are at least two areas that demand our attention: course offerings and co-curricular opportunities.

Course Offerings

Work is often a non-negotiable commitment; for a lot of first-generation students, no work means no college. As a first-generation college student, I worked over 25 hours per week and was severely limited in course options as a result. For many in this situation, finding courses that accommodate your work schedule can be both stressful and discouraging. The lack of course options can also increase the time to degree completion or otherwise necessitate difficult trade-offs, such as choosing a less desirable major to complete one’s studies on time.

Every so often, departments should consider reviewing the delivery formats, number of sections, and times and days they are offering their flagship courses. As administrators, we cannot assume that what we have always done is good enough. As student demographics change, student needs and what we must do to encourage their success change as well. With first-generation or low-income students in mind, we must consider how we can adapt current structures to foster persistence instead of hindering it. A change as simple as moving one section of a gateway course to the evening can make a huge difference.

Our task as academic or student affairs administrators is not simply to increase first-generation outreach efforts. Rather, we should also be examining how we can meet them where they are to increase their persistence, retention, and completion rates.

Co-curricular Opportunities

High-impact doesn’t have to mean high-cost. In a previous role, I served as an academic advisor for a unit that coordinated an annual education abroad trip to Europe for undergraduate students. The overarching goal was for students to build meaningful relationships with each other and to expand their knowledge of their field. Recognizing the need for lower cost alternatives that offer comparable educational value, I partnered with the institution’s alternative break program to coordinate multiple domestic service-learning trips that were still relevant to the academic field. These trips were only a fraction of the cost of the education abroad experience, had high participation rates, and allowed students to reap the benefits of a high-impact activity.

We know that some co-curricular opportunities present an enormous financial commitment for a subset of students who are less likely to have disposable income. At the same time, we know that these opportunities can be incredibly transformative. One of our charges as administrators is to think creatively about how we can provide students with the high-impact elements of these experiences without endowing individuals with an additional financial burden or having them miss out altogether. An example of this in action is The Ohio State University’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion, where they have recently prioritized making education abroad more financially accessible to the thousands of first-generation and other underrepresented students it serves.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the SCFW brief on first-generation student finances does not tell us anything we did not intuitively know. It does, however, start a conversation about what we can do. Administrators can benefit by periodically scanning for “low-hanging fruit” and “easy wins” within their span of control that translate to positive outcomes for first-generation or otherwise financially-strained students. The more we can understand our students’ relationship with finances—one of the most influential factors in their educational journey—the better equipped we can be to remove barriers to their success.