Community Building Circles for Inclusion and Belonging Among First-generation Graduate Students

Dawn Shafer, Rosemary Ferreira, Stenie Simon, Shauna Griffin, University of Maryland, Baltimore / FirstGen Forward / April 19, 2023

To enhance inclusion and belonging among the first-generation students at the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB), we launched a series of structured community building circles in 2021. While the initiative was originally specific to the School of Social Work, we expanded membership in 2022 to include students from the other graduate and professional schools that make up our institution. This blog introduces us as practitioners, identifies why we chose this model, and describes what it’s like to participate in a circle.

Who are we? As facilitators of community building circles, we take the time to share our stories because we believe that who we are in relation to this work matters. Building community means sharing of ourselves and being genuinely engaged as both facilitators and participants. Our team is small but mighty. Dawn, Shauna, and Stenie are with the School of Social Work. Dawn is a first-generation undergraduate, master’s, and PhD recipient and serves as the Associate Dean for Student Affairs; she is also a proud daughter and mother. Shauna and Stenie are both first-generation undergraduates and now Master of Social Work Students (and soon to be graduates!). Shauna does this work because it is important to pass lessons learned on to others while meeting them where they are and allowing them to be themselves. She comes from a working-class background and is proudly the first within her extended family to earn a degree. Shauna hopes to inspire her son and youngest siblings to follow in her footsteps, as many other family members already have. Stenie is a first generation Haitian American with a passion for building communities. Through the community building circles Stenie has been able to cultivate a strong connection with her peers while also being a resource when needed. Stenie shares that as a student in the pilot program in 2021, the first-gen program and circles provided a space to be seen and heard and is truly grateful for the experience as both a student and co-lead. Rosemary Ferreira is the associate director of the Intercultural Center at UMB. Through this role, Rosemary serves historically excluded and continuously marginalized students across the university’s seven schools. Rosemary also identifies as first-generation.

Why community building circles? We know that being first-generation is often an invisible identity, and that first-generation students often have additional intersecting identities. This does not stop upon entering graduate school, yet until recently there was very little acknowledgement of being first-generation within graduate and professional schools. These spaces uplift being first-generation in all its complexity. We talk about both the pressure and the privilege of being first and what it means to be a part of something greater than just your own singular journey and accomplishments.

As a health-oriented campus with a commitment to social justice and strategic plans that acknowledge the importance of engagement, belonging, and student growth and success, we wanted to ensure that we created spaces that honored these values. As such, we based this initiative on Restorative Practices (RP), which are rooted in Indigenous practices and knowledges. To learn more about the Indigenous roots of RP, please visit What is a Talking Circle: Exploring Indigenous Roots - Conflict Center. The goals of a community building circle are for each person to feel seen, heard, understood, and connected.

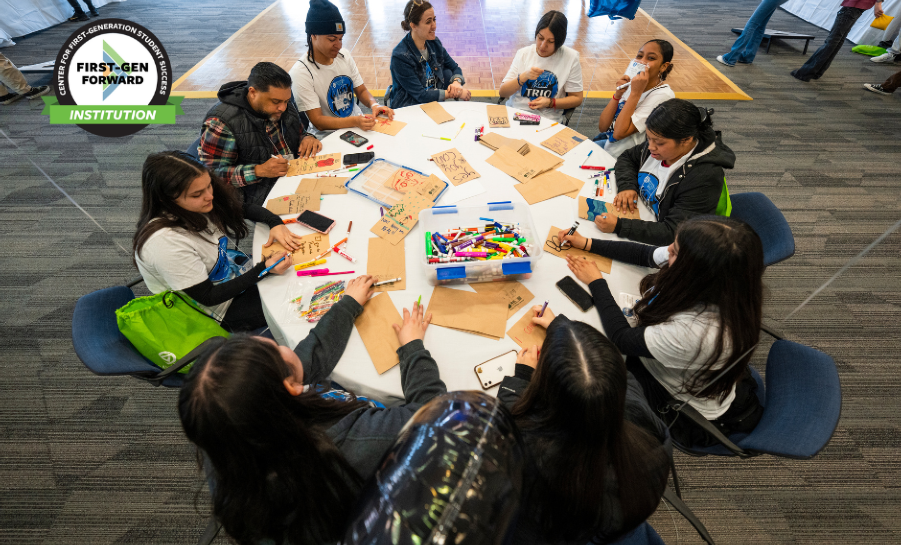

What does a circle look like? Given the goals just mentioned, the structure of a circle is vital to creating a space that cultivates bravery and safety. During the initial phase of a circle, the facilitators welcome participants, state the purpose (“to spend time in community and explore our first-generation identity”), and set agreements. Agreements are vital to providing a space in which members can be their authentic selves and know that the circle will support them. Agreements often address how people will engage with one another in the space. Some agreements include, upholding confidentiality, encouraging participants to be present, and respectfully speaking and listening. This is often followed by a mindfulness exercise to open the space. Circles use a prescribed order of speaking that remains the same throughout the activity. This allows individuals to know when they will speak and frees them to listen while others are sharing. Circles typically start with a low-risk question (such as “share something that brought you joy today” or “what’s your favorite ice cream flavor”) and build to questions that require more trust as the time progresses. While we as facilitators enter the circle space, virtually or in-person, with a set of questions, we remain open to changing our plan depending upon what is coming up in the group that day. Examples of prompts we have used at our institution include:

1. What do you need to put down to be present today and what are you hoping to pick up?

2. What does being a first-generation student mean to you?

3. Tell us about someone in your life that has been an important part of your first-generation journey.

4. What are strengths that you bring with you because of your family and community?

At our institution, we hold circles bi-weekly and consistently have a positive turnout. We have found this to be a meaningful way to build connections and foster a sense of inclusion among first-generation students.

Within our community-building circles we acknowledge that first-generation identity does not end at the culmination of the undergraduate experience. Rather, navigating graduate and professional school as a first-generation student can be especially challenging because of the lack of resources and opportunities for connection. At UMB, we have found that the model of community-building circles has supported our efforts to raise visibility of first-generation student identity within the graduate and professional school setting. We have also found that storytelling can serve as a vehicle for co-creating knowledge and building a sense of belonging and community. We hope that our story can help guide other higher education institutions to engage and foster community among first-generation graduate and professional students.