Growing a First-generation Institutional Identity from the Ground Up

Colin D. Fewer, Purdue University Northwest / FirstGen Forward / May 17, 2023

As more institutions recognize first-generation status as being a unique identity, and uncovering the manual of best practices that comes with that identity, I've been fascinated by the many different ways that institutions have entered the first-generation space: some as top-down mandates; some as grassroots movements. Purdue University Northwest (PNW) is an institution in a diverse metropolitan area, where 54% of students are first-generation. Our first-generation initiatives started small, but soon took on an incredible life of their own, changing the face of the institution along with them.

First-generation initiatives at PNW began with an ad-hoc group of mostly first-generation staff who were inspired by NASPA's First-gen Forward and First Scholars initiatives. The Assistant Vice Chancellor responsible for our TRIO programs led the initiative at first, gathering a committee of campus leaders to complete the First-Gen Forward application. Looking back now, I remember how relatively unfamiliar the vocabulary of first-generation seemed to some of us. We were used to talking about our student demographics in the familiar terms of race and ethnicity, Pell-eligiblity, gender identification, and so on. We had been focused for the past few years on attaining Hispanic Serving Institution status, and had recently hired a full-time director to manage that process and build bridges to the Hispanic communities in our area. We were also turning our attention to Black communities, recruiting more aggressively and having intentional conversations about creating belonging among Black students. We knew the research on first-gen students, but where did the first-generation identity fit into these strategic priorities? It was a term that applied to so many of our students that it might become meaningless. As our students negotiated the already complex intersectionalities of their lives, while trying to succeed as students and emerging professionals, could we ask them to wear one more hat? Was "first generation" something they would want to claim, along with the identities they had owned all their lives? More than a few of us in those initial meetings had doubts, including me—but we were interested, and curious. We saw other institutions successfully integrating first-gen into their identities and missions. So we committed to starting the journey and seeing where it led.

First-gen was a hat—or a cord—that they wanted to own. They were proud of it.

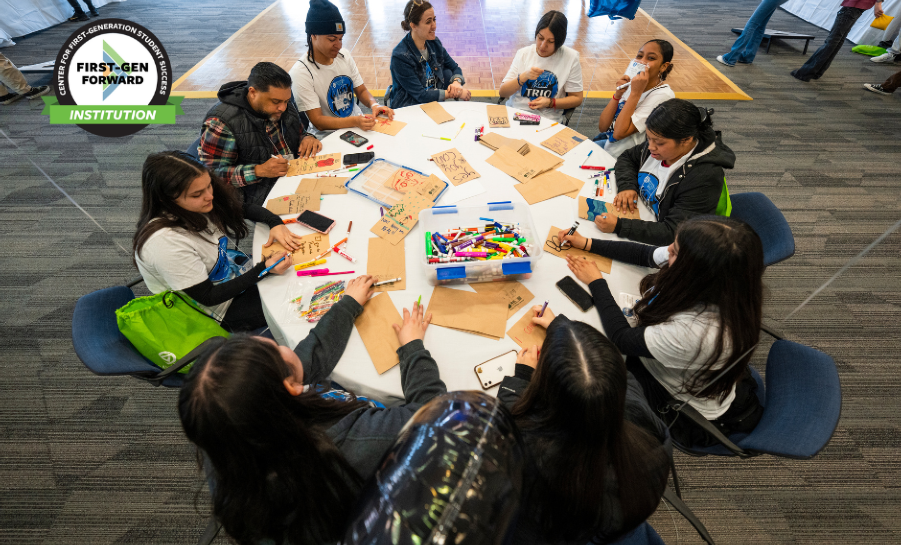

We started relatively small in Fall of 2022, following the NASPA program and listening carefully to the experiences and ideas of other schools in our cohort. It was all volunteer and all ad-hoc: we kept our senior leadership in the loop, but everyone contributed the time they had in between their other projects and priorities. We tried to take care of the little things—we designed a graphic celebrating first-gen pride and started putting it in email signatures, stickers and other small swag items. We had some successful events, including a first-gen panel for PNW students as well as ETS and Upward Bound students. And, significantly, we managed to get a first-gen recognition into our December commencement script. We ordered silver cords to distribute for the students to wear at the ceremony. We really weren't sure how this was going to go, mind you, since we had not been promoting first-generation identity for very long that semester. But slowly but surely, students started showing up to pick up the cords. We gave away a little over 200 in the end—not bad, we told ourselves, and it'll create momentum for next semester. For whatever reason, we were mostly thinking of this as a small project, an easy win to pave the way for bigger things down the road.

On commencement day, many more students picked up cords at check-in, along with faculty and staff. I was surprised to see faculty members I had known for years wearing the silver cords. All of a sudden, it seemed like silver cords were everywhere. At the appointed time during the ceremony, for the first time in 76 years, PNW invited first-generation graduates--as well as first-gen faculty and staff--to stand and be recognized for their hard work and achievements.

They all stood up. A long moment passed, probably shorter in reality than it felt, as everyone looked at each other. It was an extremely diverse group—but all first-gen. The students had answered us. First-gen was a hat—or a cord—that they wanted to own. They were proud of it. And every member of the Chancellor's cabinet could feel from the stage the importance of that moment. The Purdue trustee who was in attendance said later that it was his favorite part of the ceremony.

What had started as an ad-hoc project suddenly had a life of its own, and real momentum. When the AVC for TRIO left to pursue other opportunities, we took the opportunity to rewrite the job description and specifically to add a mandate for first-generation student success: Executive Director for Diversity, Inclusivity, and Belonging. We committed $15,000 to a microgrant program for faculty and staff developing or redesigning course content with a first-gen focus, and the response was fantastic. We gave away over 400 cords at the Spring 2023 commencement, and are looking forward to our first First-Gen Grad pre-commencement celebration next semester. It's been an extraordinary and rewarding journey for the staff involved, and especially for the students.