First-generation Student Success: Proximity Does Not Equal Advocacy

Whitnee Boyd Ed.D., Texas Christian University / FirstGen Forward / November 09, 2021

Dr. Whitnee Boyd, is coordinator of special projects at Texas Christian University and serves as chair of the Advocacy Group for the Center for First-generation Student Success in Washington, DC.

On November 8, 2021, the Council for Opportunity in Education (COE) and the Center for First-generation Student Success will lead the national efforts of the fifth annual First-Generation College Celebration. On campuses across the country, higher education institutions will host panels, listening sessions, celebration events, photo booths, and giveaways in honor of the accomplishments of first-generation students.

This year, in addition to celebrating the accomplishments of our first-generation students and alumni, I would like to ask that we–a collective of practitioners, faculty, administrators, community-based organizations, business leaders, families, and education systems at all levels–include a call to advocacy as part of our celebrations.

The numbers make it clear that we are not doing enough to build a system of support for first-generation students in this country. Despite the fact that approximately one-third of all current students identify as first-generation, our system of education has not yielded the same outcomes for first-generation college students as their continuing-generation college students peers.

A recent study from the Pew Research Center tells us that students whose parent(s) have a college degree, compared to those whose parent(s) do not, have a higher access to wealth, graduate at higher rates, are less likely to incur educational debt, among other factors (2021). And just last week, a report from Strada indicated “first-generation students experience worse outcomes compared to their peers with college-educated parents, trailing by 13 percentage points in achieving income over $40,000, 6 percentage points in feeling education was worth the cost, and 8 percentage points in feeling that education helped them to achieve their goals.”

The numbers make it clear that we are not doing enough to build a system of support for first-generation students in this country.

These findings, and many others just like them, continue to speak to how providing access to our colleges and universities is not enough. We must actively create pathways for first-generation students to thrive, which means removing barriers allowing them to get the maximum benefit from being in college (Schreiner, 2010). We must become true advocates for first-generation student success.

In order to become true advocates, it’s imperative that we differentiate between proximity and advocacy. Our proximity to people, spaces, and populations does not make one an advocate.

My first role as a higher education professional was in a TRiO program, Student Support Services, working each day alongside students who were the first in their families to attend college. My experience as a Black woman studying at a historically white institution made me aware of certain inequities and helped me to find my voice to speak out and navigate in spaces that were not necessarily built with me in mind.

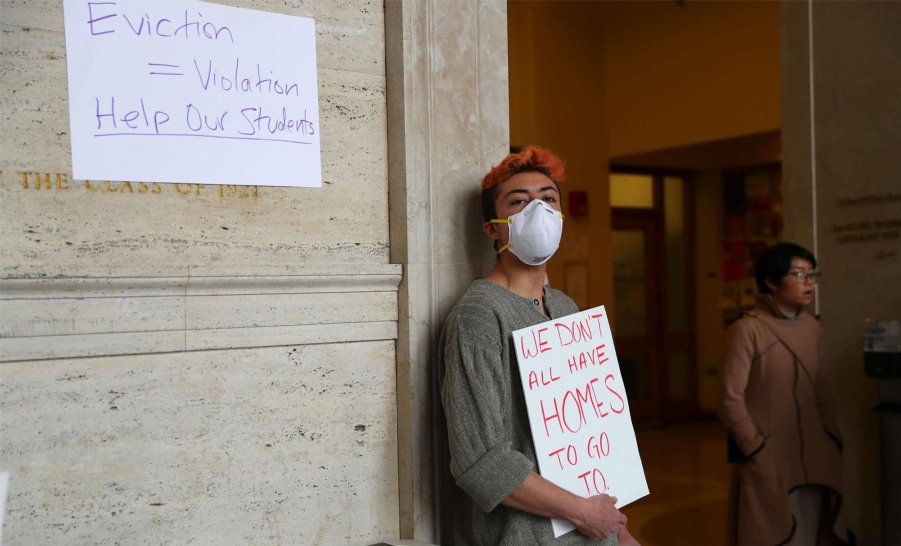

Image Credit: missoulian.com

To conflate proximity and advocacy means to promote the work of practitioners supporting first-generation students without giving them the budgetary and human capital needed. It means holding up first-generation students as a shining example of an institution’s diversity and inclusion efforts without having the tools and strategies in place to help them succeed.

It’s time to move forward. This date marks the anniversary of the signing of the 1965 Higher Education Act, which has helped millions of first-generation students persist to degree completion. So, like President Johnson did when proposing the legislation 56 years ago, we must take the steps necessary to be true advocates.

If we use first-generation student statistics to help market our programs, institutions, and workplaces, we should ensure they have a seat at the table when key decisions are made that impact the community and culture.

Advocate with intent

First-generation students enter our schools, communities, and workplaces with a level of drive and determination that is unmatched. It is important that we act with intent to understand that, while they may have some things they share, there are many nuances to identity that shape their experience.

If we use first-generation student statistics to help market our programs, institutions, and workplaces, we should ensure they have a seat at the table when key decisions are made that impact the community and culture. We should critically assess the way in which we include their voices in all spaces by ensuring they are represented.

A key thing in identifying these voices is understanding that first-generation college students come to us with many intersecting identities that play a major role in how they navigate. In a landscape study conducted by the Center, the researchers argue that understanding the concept of students being “first-gen plus,” allows us to ensure our services and resources are designated and designed appropriately (Whitley, Benson, & Wesaw, 2018).

It is essential that we are hyper-aware of the nuances of the “plus” allowing us to explore how the lived experiences of a first-generation student who is also a student of color and/or has a learning difference may be similar in ways yet vastly different than a first-gen white student from a rural community. We must be keenly aware of this and intentionally amplify the voices and lived experiences of our first-generation students in order to help us make decisions, remove barriers, set policies, and create opportunities.

Advocate with dissent

In a world where many things become polarized, we often shy away from dissent. I argue that healthy dissent is where we begin to identify problems and create equitable solutions. To consider oneself as an advocate for first-generation college students, I firmly believe you must be willing to offer dissent.

Without dissent, we will not improve outcomes and we remain in a stagnant place with our services and commitment to the success of first-generation students. Using your positionality, privilege, and access to power to speak up and out for this group is advocacy in its purest form. Advocates who offer dissent have led to increased investment in financial aid, dedicated budgets for enhancing support-based programs, training and development for faculty and staff, and shifting systematic ways of challenging the use of deficit-thinking and language.

I encourage you to offer dissent because access is simply not enough. When committing to serving students and families, we must do so beyond the point of access.

This does not result in graduation or a positive experience that was inclusive. Dissent allows us to live out the mission and values of our organizations that help us to stand against exclusionary behavior and leads us to creating a culture that values belonging.

Please join me in advocating with intent and dissent on behalf of first-generation students, on November 8 and beyond.