WHY FIRST-GEN HEALTH PROFESSIONALS ARE ESSENTIAL TO IMPROVING OUR NATION’S HEALTH CARE

Laura M. Wagner Ph.D., RN, FAAN, University of California, San Francisco / FirstGen Forward / December 13, 2019

Imagine for a moment you are a first-generation to college health professions student aspiring to be a dentist, a nurse, a doctor, a pharmacist, a physical/occupational/speech therapist, or social worker. You thrive when you’re talking with patients in your clinical rotations and are passionate about one day returning to your community to improve the health of that community. Guided by your upbringing, you may have experienced social or economical circumstances that help you better understand and empathize with the struggles and barriers others face and how it impacts their health. You may have witnessed friends or family members who have experienced homelessness, incarceration, a disabling occupational injury, or language barriers.

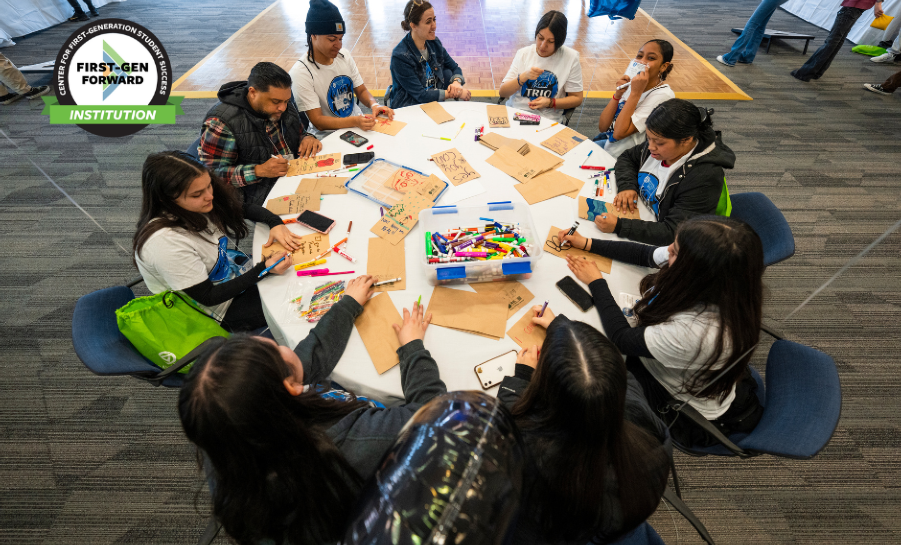

As an inaugural First Forward Institution, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is leading the way to foster the career development for first-gen health professions students. Thirty percent of the student population at UCSF identifies as first-gen. UCSF is among the first in healthcare to raise the topic of nurturing the careers of future health care providers. In 2017, Dr. Laura Wagner founded the FirstGenRN program which supports first-gen students attending nursing school. The FirstGenRN program has created a space where future nurses can feel supported and norming their challenges. In addition to the FirstGenRN program, UCSF has a robust First Generation Support Services that solely supports graduate and professional students entering into the health professions.

First-gen health professionals are needed now more than ever. With this need, there is a responsibility for universities and colleges to provide the best support so first-gen students succeed in their academic journey.

The non-White percentage of older adults is also expected to double. Over 38 million Americans are living in poverty, many whom are high utilizers of health care services (Semega, Kollar, Creamer, & Mohanty, 2019). Furthermore, social determinants of health, the conditions under which someone lives, play an increasing role in a patient’s health and health outcomes. In other words, we are going to need to double our efforts to enhancing the diversity of the health professions workforce so the health workforce can mirror the shifting population.

First-gen health professionals are needed now more than ever. With this need, there is a responsibility for universities and colleges to provide the best support so first-gen students succeed in their academic journey.

We invite you to attend our inaugural symposium, First-Gen Health, on November 5-6, 2020 where you can learn how to best support health professions students who are the future of healthcare. Click here to save the date.

References

Blanchard, J., Nayar, S., Lurie, N. (2007). Patient–provider and patient–staff racial concordance and perceptions of mistreatment in the health care setting. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(8), 1184-1189.

Charlot M., Santana, M.C., Chen, C.A., Bak, S., Heeren, T.C., Battaglia, T.A…., Freund, K.M. (2015). Impact of patient and navigator race and language concordance on care after cancer screening abnormalities. Cancer, 121(9), 1477-1483.

Cooper, L.A., Roter, D.L., Johnson, R.L., Ford, D.E., Steinwachs, D.M., Powe, N.R. (2003). Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139 (11), 907-915.

LaVeist, T.A., Nuru-Jeter, A., Jones, K.E. (2003). The association of doctor- patient race concordance with health services utilization. Journal of Public Health Policy, 24(3-4), 312-323.

National Conference of State Legislatures (2014). Racial and ethnic health disparities: Workforce diversity. Diversity in the healthcare workforce. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/documents/health/Workforcediversity814.pdf

Saha S., Taggart, S.H., Komaromy, M., & Bindman, A.B. (2000). Do patients choose physicians of their own race? Health Affairs, 19(4), 76-83.

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Creamer, J., & Mohanty, A. (2019). U.S. Census Bureau, Current population reports, P60-266, Income and poverty in the United States: 2018, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Thornton, R.L., Powe, N.R., Roter, D., Cooper, L.A. (2011). Patient-physician social concordance, medical visit communication and patients' perceptions of health care quality. Patient Education and Counseling, 85(3), e201-208.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (2017). Sex, race, and ethnic diversity of U.S, health occupations (2011-2015), Rockville, Maryland.